In Conversation - Weaving History Into Clothing With John Alexander Skelton

In 1998, the Skelton family was on holiday in the Loire Valley of France. It was a hot summer day when an 8-year-old John Alexander Skelton wearily followed his family as they visited one after another cultural landmark. Just a few hours previously they had been in Bayeux, a town famous for holding the roughly 950-year-old namesake tapestry of British origin; then they walked into the Abbaye Royale de Fontevraud.

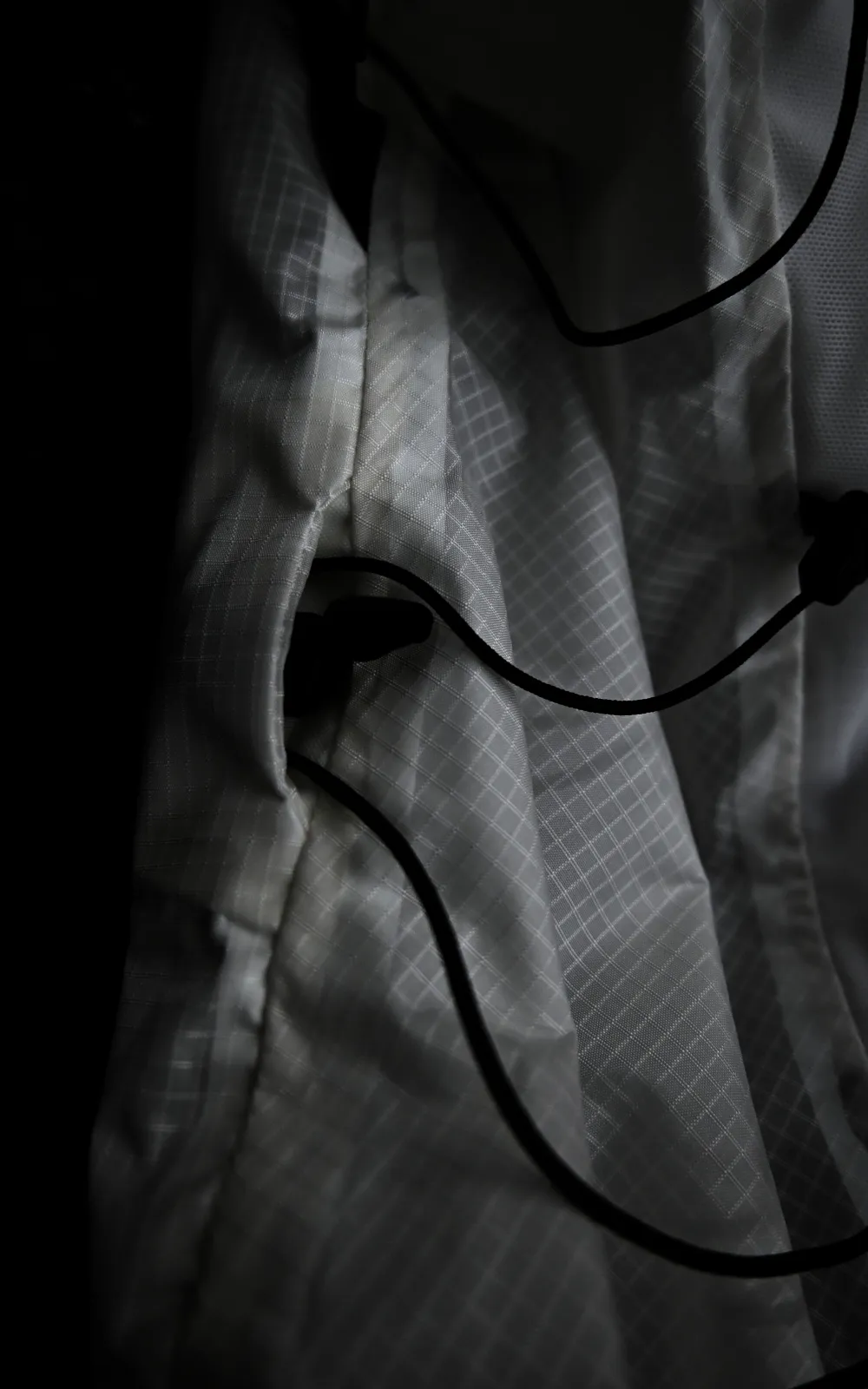

Young John Alexander came up to Richard The Lionheart’s tomb (fashioned in his likeness, though no longer holding his remains) and he was awe-struck. The intensity of the experience was magnified by the coolness of the air inside the abbey in comparison to the sweltering heat outside; its dilapidated stones appeared black in contrast to the brightness. The nave and its catacombs, as he remembers them, were far from pristine; yet in his eyes, cracked floors and eye-level surfaces polished by the hands of the centuries only enhanced the grandeur and exquisiteness of its construction.

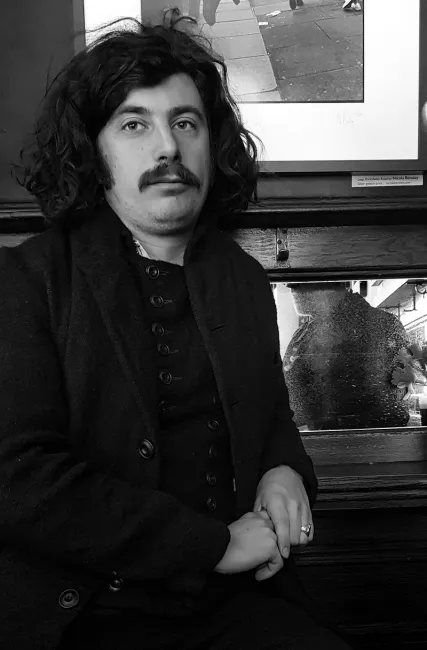

Today John Alexander Skelton is one of the most relevant young designers in Britain and around the world. His quirky, historically based designs offer a strong counterpoint to streetwear; his slow-crafted and lovingly detailed garments are the perfect antidote to the fast-fashion pandemic.

Campbell and I sit on salvaged Victorian chairs across the table from John and his partner Yue in their bright central London studio. There are many things Darklands shares in common with John – not least our love of history and politics, but also a certain intensity, rebelliousness and appreciation for the uncanny. It has always been a mandate for Darklands to keep at the forefront of the Avant-Garde, seeking out designers with unusual approaches who are able to find their own sources of inspiration, materials and concepts.

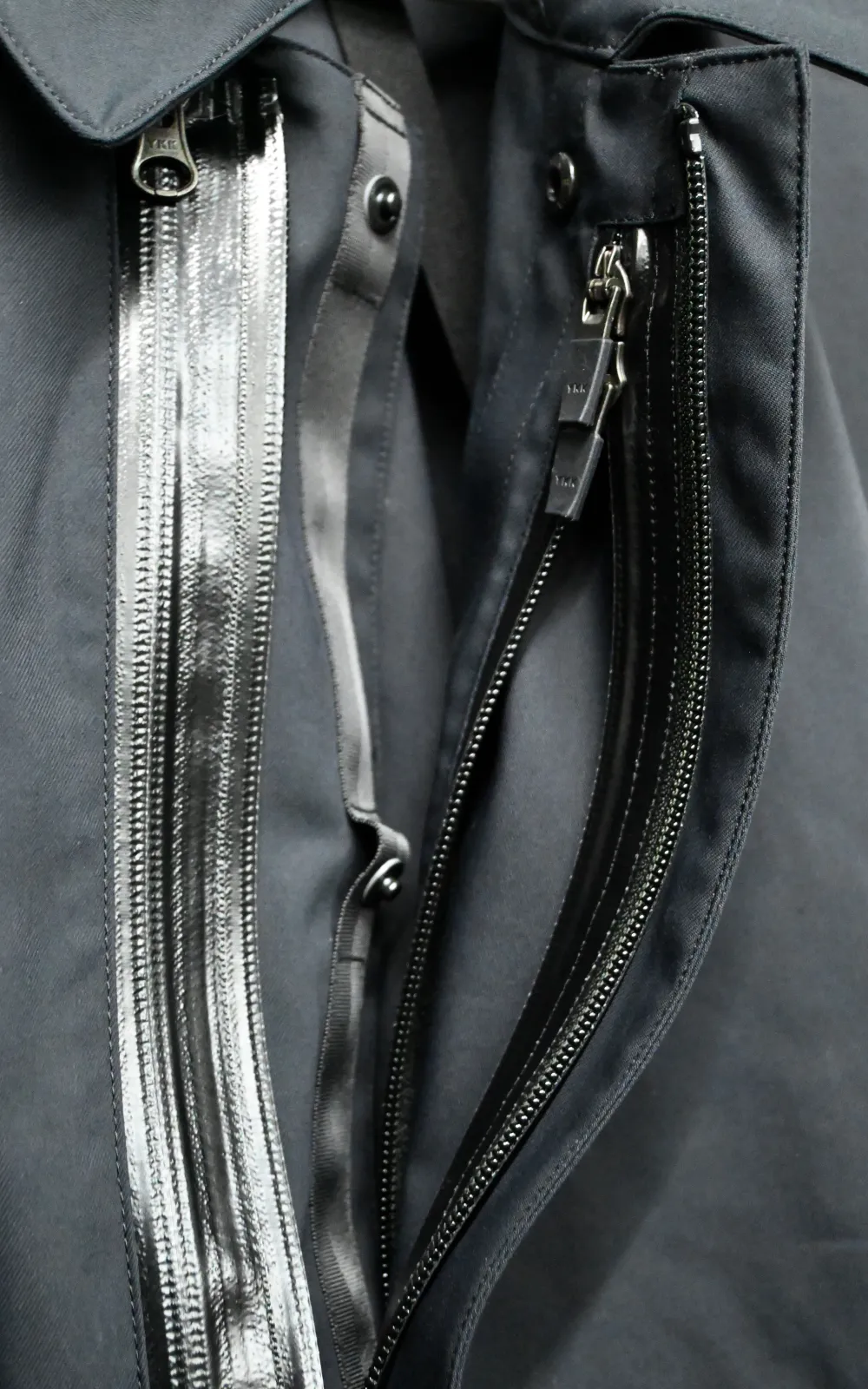

John, like many young designers, started his company with very little initial investment. He had no financial backer and was “very stubborn in not taking help in funds”, but he was resolute to make it work. Through a combination of good mentorship, solid knowledge of his target market and a heaping dose of ingenuity, John has managed to build a viable independent business: “I was determined to do what I wanted to do, so I had to be very creative in the way that I made the collection and sold it. My work is so labor-intensive and involved that I knew I needed to manage my time very well, and I knew that I need to sell it because otherwise I couldn’t carry on”. One of the strategies he devised for keeping to a small budget was upcycling: “it’s something that started off almost as a business decision, because I knew I needed to use my own creativity to make something luxury out of something that was accessible for me. When you are able to reuse and remake, you can bring something new to life and change the perception of its value. That was important for me, and it has shaped what my brand looks like now”.

This relentless determination to work under his own terms came in handy when faced with the pressures that the world of fashion brings onto promising designers. As John’s company began to attract more attention, he felt prepared to deal with it because his vision and path were already clear: He was not “aiming to please press people” and was comfortable removing himself from the gerbil-wheel of the traditional fashion world, minimizing and selecting projects to be involved with, publications to be associated with, as well as, fashion shops he was willing to sell to. This in turn allowed him to pursue his vision with a clearer creative mind and keep his company independent, without ever compromising on quality.

Naturally, this did not entail less work or less pressure – perhaps quite the contrary. John admits to quickly realising that his craft requires always a certain level of intensity, which is not easy to maintain and demands “great amounts of stamina”. Yet he believes that finding shortcuts or ways around the hard work is what leads to a creative venture’s ultimate demise. One of the ways in which he keeps this energy flowing is by concentrating on those themes which he is most passionate about: politics and social structures, and the sociopolitical and historical side of Britain.

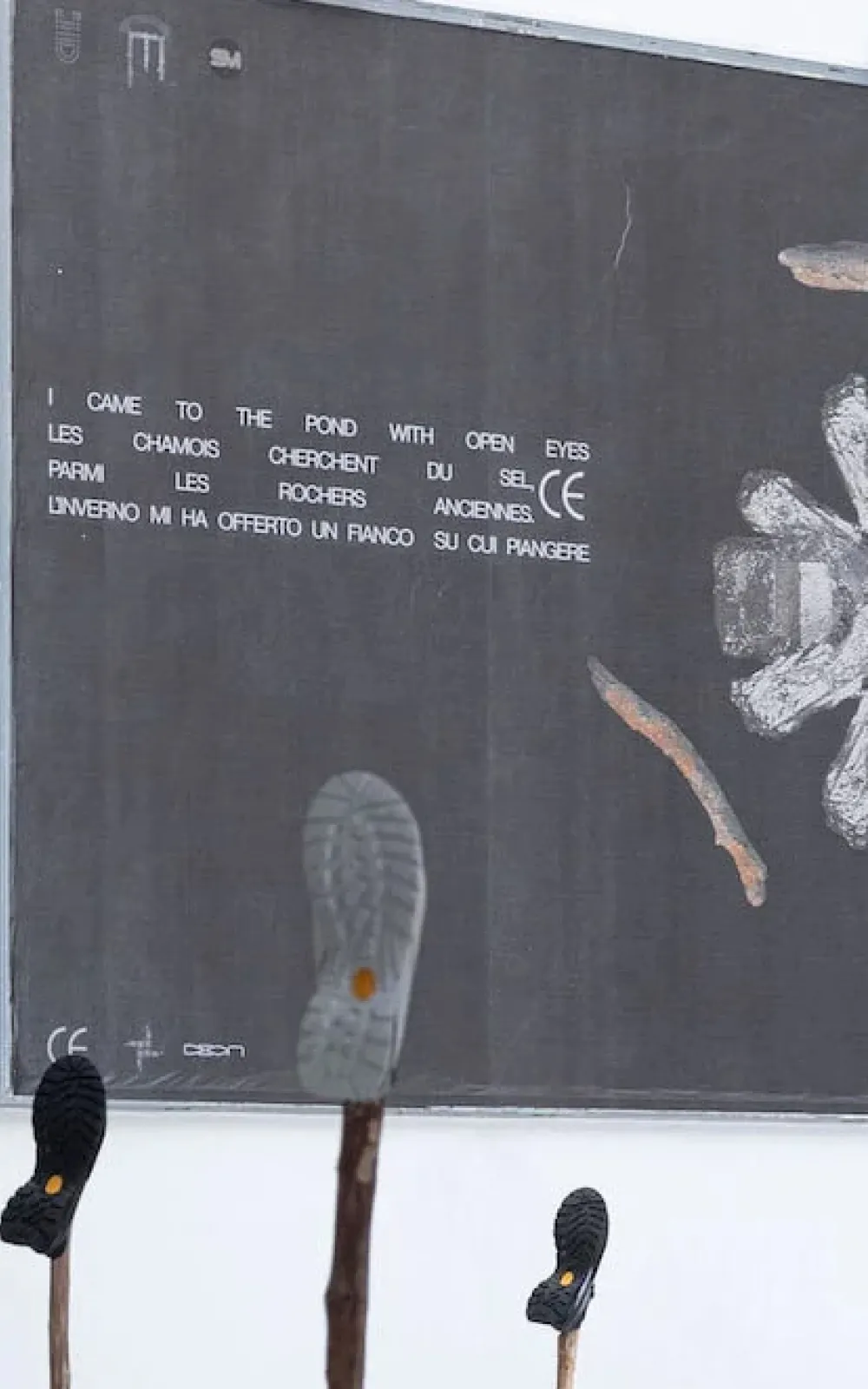

John’s collections have a very British sensibility to them. He explains to us that Britain is a country made up of many different peoples throughout its history: “people from all over the world have come here, from the Vikings and the Roman Empire up to our current times, and influences from all over the world make up what is now supposedly British”. John likes to explore deeply into the more niche and obscure things within Britishness and forge his collections within those ideas and events that happened in the past, yet retaining their modern relevance. The result of this approach is a strong narrative that runs from the clothing to the presentation: a whole vision that brings the spectator (and the wearer) into John’s world and allows him to get involved, thus gaining a deeper understanding of the clothing physically, as well as, conceptually.

Fashion, like film and literature, requires an element of fantasy in order to be truly successful as an immersive experience, and undoubtedly his annual fashion presentations achieve an otherworldy environment. Campbell asks him how this came about. Was it a conscious reaction to the conventional Fashion Show?

John: “I realised, just from going to a few shows that they were incredibly boring and I didn’t really understand why a buyer would want to attend one of those shows… because they are going to see the clothing anyway (Campbell laughs, and nods in agreement). Maybe movement is one part of seeing it on a model, but that really is the only thing. If the designer is not going to show the world that his clothes are supposed to inhabit, then I don’t know what he will achieve with it.”

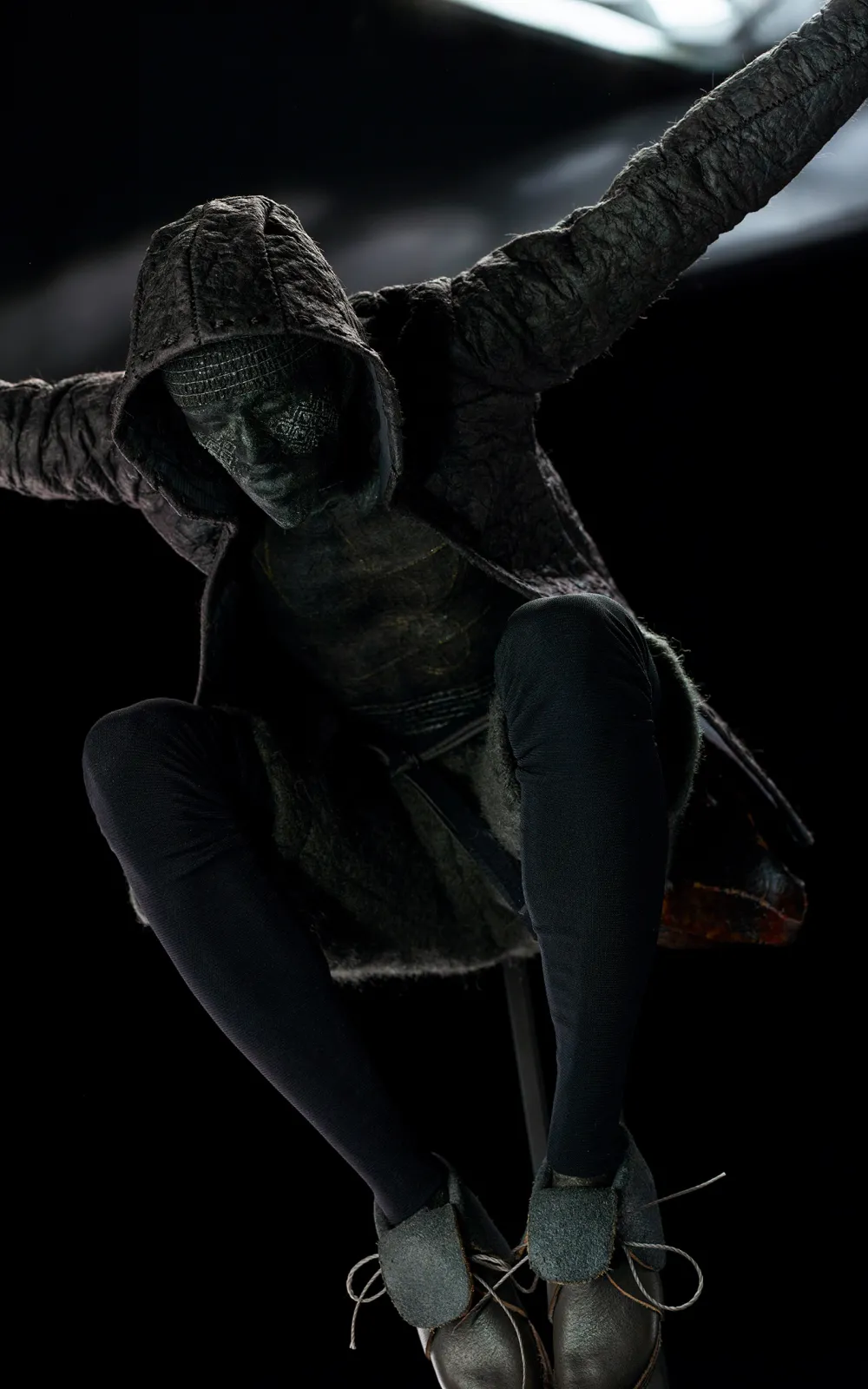

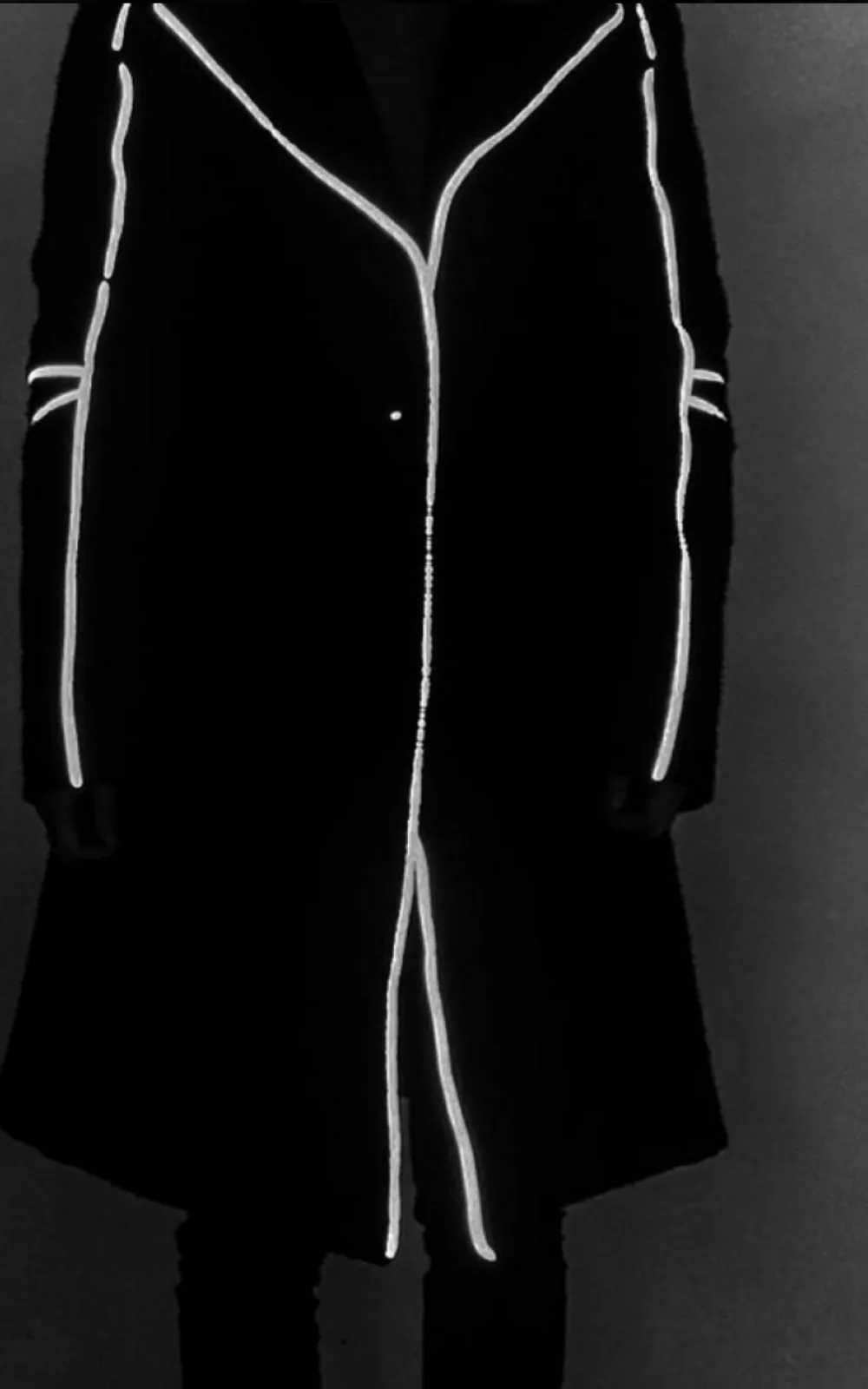

Love them or not, John’s presentations are anything but boring. His latest show was held in a 17th Century pub tucked away in London’s financial district, and featured a cast of street-scouted models of various ages and walks of life. It was an intense experience: the performers lurched, kneeled, stomped; they chanted, and among those chants they hummed or screamed. Some wielded planks, one flashed his antique revolver. In this candlelit chaos permeated by the scent of burning wood and dried petals, we were plunged headfirst into a magnified impression of London City’s turbulent past. As if in a shamanistic ritual, the garments seemed not to have been produced, but conjured up.

John: “History allows a form of escapism and a form of fantasy as well, and whilst I would like to stay as close to the narrative that I am working within, there’s always room for filling in the gaps and projecting what you want that time to look like, or be.”

Not unlike the Bayeux Tapestry and the Abbey of Fontevraud, art provides us with countless examples of this statement. Time and time again, artists reimagine and reinterpret the past, forging a new identity in the process. John has achieved precisely that: an aesthetic that is truly original and unmistakably his. He has an integrity that runs from the drawing board to the finished product, unconcerned with conforming to any standards but his own. John proudly describes his working process as “selfish” in the sense that, from the start, he did not “really care about what people thought about (his designs), as long as they were completely true to (him)”.

Words by Estefania Campillo